Introduction

Within Europe, the method usually adopted for the economic evaluation of highway schemes, termed cost-benefit analysis, utilises the net present value technique where the costs and benefits of the scheme are discounted over time so that they represent present day values. Using this method, any proposal having a positive net present value is economically sustainable in absolute terms. Where competing project options are being compared, assuming they are being used in identical capacities over the same period, the one with the numerically larger NPV is selected (i.e. the one that is less negative or more positive). A brief historical background to the method has already been given in Chapter 1. The main steps in the technique involve the listing of the main project options, the identification and discounting to their present values of all relevant costs and benefits required to assess them, and the use of economic indicators to enable a decision to be reached regarding the proposal’s relative or absolute desirability in economic terms.

Identifying the main project options

This is a fundamental step in the CBA process where the decision-makers compile a list of all relevant feasible options that they wish to be assessed. It is usual to include a ‘do-nothing’ option within the analysis in order to gauge those evaluated against the baseline scenario where no work is carried out. The ‘dominimum’ option offers a more realistic course of action where no new highway is constructed but a set of traffic management improvements are made to the existing route in order to improve the overall traffic performance. Evaluation of the ‘do-nothing’ scenario does however ensure that, in addition to the various ‘live’ options being compared in relative terms, these are also seen to be economically justified in absolute terms, in other words their benefits exceed their costs.

The term ‘feasible’ refers to options that, on a preliminary evaluation, present themselves as viable courses of action that can be brought to completion given the constraints imposed on the decision-maker such as lack of time, information and resources.

Finding sound feasible options is an important component of the decision process. The quality of the final outcome can never exceed that allowed by the best option examined. There are many procedures for both identifying and defining project options. These include:

· Drawing on the personal experience of the decision-maker himself as well as other experts in the highway engineering field

· Making comparisons between the current decision problem and ones previously solved in a successful manner

· Examining all relevant literature.

Some form of group brainstorming session can be quite effective in bringing viable options to light. Brainstorming consists of two main phases. Within the first, a group of people put forward, in a relaxed environment, as many ideas as possible relevant to the problem being considered. The main rule for this phase is that members of the group should avoid being critical of their own ideas or those of others, no matter how far-fetched. This non-critical phase is very difficult for engineers, given that they are trained to think analytically or in a judgmental mode (Martin, 1993). Success in this phase requires the engineer’s judgmental mode to be ‘shut down’. This phase, if properly done, will result in the emergence of a large number of widely differing options.

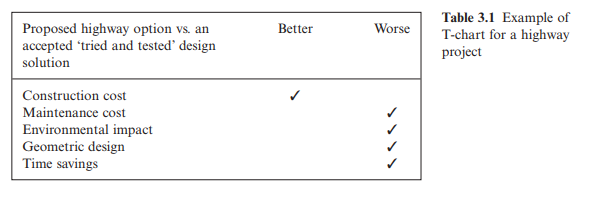

The second phase requires the planning engineer to return to normal judgmental mode to select the best options from the total list, analysing each for technological, environmental and economic practicality. This is, in effect, a screening process which filters through the best options. One such method is to compare each new option with an existing, ‘tried-and-tested’ option used in previous similar highway proposals by means of a T-chart (Riggs et al., 1997). The chart contains a list of criteria which any acceptable option should satisfy. The option under examination is judged on the basis of whether it performs better or worse than the conventional option on each of the listed criteria. It is vital that this process is undertaken by highway engineers with the appropriate level of experience, professional training and local knowledge in order that a sufficiently wide range of options arise for consideration.

An example of a T-chart is shown in Table 3.1.

In the example in Table 3.1, the proposed option would be rejected on the basis that, while it had a lower construction cost, its maintenance costs and level of environmental intrusion and geometric design, together with its low level of

time savings for motorists, would eliminate it from further consideration. The example illustrates a very preliminary screening process. A more detailed, finer process would involve the use of percentages rather than checkmarks. The level of filtering required will depend on the final number of project options you wish to be brought forward to the full evaluation stage.