Aqueduct, (from Latin aqua + ducere, “to lead water”), conduit built to convey water. In a restricted sense, aqueducts are structures used to conduct a water stream across a hollow or valley. In modern engineering, however, aqueduct refers to a system of pipes, ditches, canals, tunnels, and supporting structures used to convey water from its source to its main distribution point. Such systems generally are used to supply cities and agricultural lands with water. Aqueducts have been important particularly for the development of areas with limited direct access to fresh water sources. Historically, aqueducts helped keep drinking water free of human waste and other contamination and thus greatly improved public health in cities with primitive sewerage systems.

Although the Romans are considered the greatest aqueduct builders of the ancient world, qanāt systems were in use in ancient Persia, India, Egypt, and other Middle Eastern countries hundreds of years earlier. Those systems utilized tunnels tapped into hillsides that brought water for irrigation to the plains below. Somewhat closer in appearance to the classic Roman structure was a limestone aqueduct built by the Assyrians about 691 BCE to bring fresh water to the city of Nineveh. Approximately two million large blocks were used to make a water channel 10 metres (30 feet) high and 275 metres (900 feet) long across a valley.

The elaborate system that served the capital of the Roman Empire remains a major engineering achievement. Over a period of 500 years—from 312 BCE to 226 CE—11 aqueducts were built to bring water to Rome from as far away as 92 km (57 miles). Some of those aqueducts are still in use. Only a portion of Rome’s aqueduct system actually crossed over valleys on stone arches (50 km out of a total of about 420 km); the rest consisted of underground conduits made mostly of stone and terra-cotta pipe but also of wood, leather, lead, and bronze. Water flowed to the city by the force of gravity alone and usually went through a series of distribution tanks within the city. Rome’s famous fountains and baths were supplied in that way. Generally, water was not stored, and the excess was used to flush out sewers to aid the city’s sanitation.

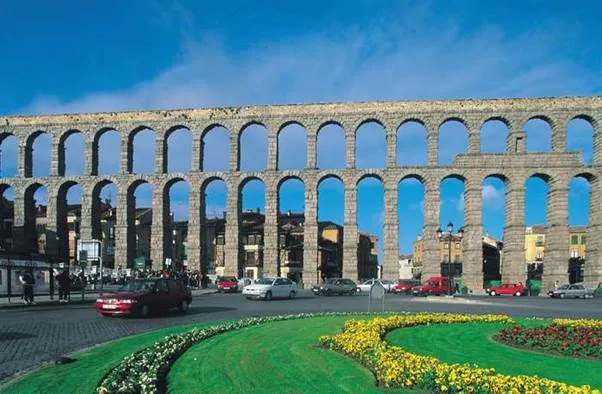

Roman aqueduct, Segovia, Spain.

Roman aqueducts were built throughout the empire, and their arches may still be seen in Greece, Italy, France, Spain, North Africa, and Asia Minor. As central authority fell apart in the 4th and 5th centuries, the systems also deteriorated. For most of the Middle Ages, aqueducts were not used in western Europe, and people returned to getting their water from wells and local rivers. Modest systems sprang up around monasteries. By the 14th century, Brugge, with a large population for the time (40,000), had developed a system utilizing one large collecting cistern from which water was pumped, using a wheel with buckets on a chain, through underground conduits to public sites.

Caesarea: Roman aqueduct

Major advances in public water systems since the Renaissance have involved the refinement of pumps and of pipe materials. By the late 16th century, London had a system that used five waterwheel pumps fastened under the London Bridge to supply the city, and Paris had a similar device at Pont Neuf that was capable of delivering 450 litres (120 gallons) per minute. Both cities were compelled to bring water from greater distances in the next century. A private company built an aqueduct to London from the River Chadwell, some 60 km (38 miles) distant, that utilized more than 200 small bridges built of timber. A French counterpart combined pumps and aqueducts to bring water from Marly over a ridge and into an aqueduct some 160 metres (525 feet) above the Seine.

One of the major innovations during the 18th and 19th centuries was the introduction of steam pumps and the improvement of pressurized systems. One benefit of pumping water under pressure was that a system could be built that followed the contours of the land; the earlier free-flowing systems had to maintain certain gradients over varied terrain. Pressurization created the need for better pipe material. Wood pipes banded with metal and protected with asphalt coating were patented in the United States in 1855. Before long, however, wood was replaced first by cast iron and then by steel. For large water mains (primary feeders), reinforced concrete became the preferred construction material early in the 20th century. Ductile iron, a stronger and more elastic type of cast iron, is one of the most common materials now used for smaller underground pipes (secondary feeders), which supply water to local communities.

Saint-Clément Aqueduct

Modern aqueducts, although lacking the arched grandeur of those built by the Romans, greatly surpass the earlier ones in length and in the amount of water they can carry. Aqueduct systems hundreds of miles long have been built to supply growing urban areas and crop-irrigation projects. The water supply of New York City comes from three main aqueduct systems that can deliver about 6.8 billion litres (1.8 billion gallons) of water a day from sources up to 190 km (120 miles) away. The aqueduct system in the state of California is by far the longest in the world. The California Aqueduct conveys water about 700 km (440 miles) from the northern (wetter) part of the state into the southern (drier) part, yielding more than 2.5 billion litres (650 million gallons) of water a day.