Distance is one of the fundamental measurements in surveying. Although frequently measured as a spatial distance (sloping distance) in three-dimensional space, usually it is the horizontal component which is required.

Distance is required in many instances, e.g. to give scale to a network of control points, to fix the position of topographic detail by offsets or polar coordinates, to set out the position of a point in construction work, etc.

The basic methods of measuring distance are, at the present time, by taping or by electromagnetic (or electro-optical ) distance measurement, generally designated as EDM. For very rough reconnaissance surveys or approximate estimates pacing may be suitable.

For distances over 5 km, GPS satellite methods, which can measure the vectors between two points accurate to 1 ppm are usually more suitable.

TAPES

Tapes come in a variety of lengths and materials. For engineering work the lengths are generally 10 m, 30 m, 50 m and 100 m.

Linen or glass fibre tapes may be used for general use, where precision is not a prime consideration. The linen tapes are made from high quality linen, combined with metal fibres to increase their strength. They are sometimes encased in plastic boxes with recessed handles. These tapes are often graduated in 5-mm intervals only.

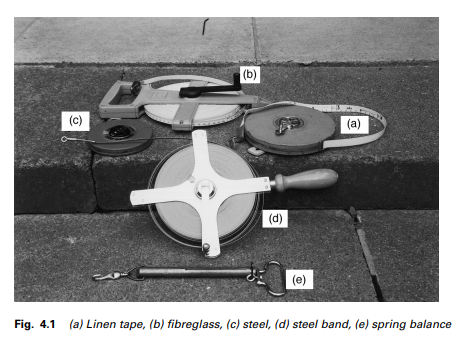

More precise versions of the above tapes are made of steel and graduated in millimetres. For high-accuracy work, steel bands mounted in an open frame are used. They are standardized so that they measure their nominal length at a designated temperature usually 20◦C and at a designated applied tension usually between 50 N to 80 N. This information is clearly printed on the zero end of the tape. Figure 4.1 shows a sample of the equipment.

For the most precise work, invar tapes made from 35% nickel and 65% steel are available. The singular advantage of such tapes is that they have a negligible coefficient of expansion compared with steel, and hence temperature variations are not critical. Their disadvantages are that the metal is soft and weak, whilst the price is more than ten times that of steel tapes. An alternative tape, called a Lovar tape, is roughly, midway between steel and invar.

Much ancillary equipment is necessary in the actual taping process, e.g.

(1) Ranging rods are made of wood or steel, 2 m long and 25 mm in diameter, painted alternately red and white and have pointed metal shoes to allow them to be thrust into the ground. They are generally used to align a straight line between two points.

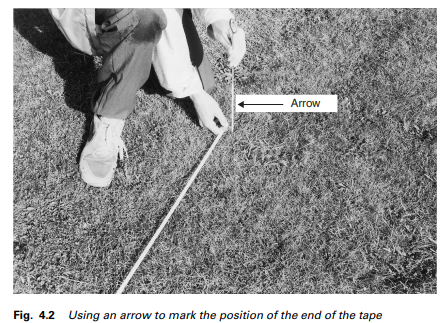

(2) Chaining arrows made from No. 12 steel wire are also used to mark the tape lengths (Figure 4.2).

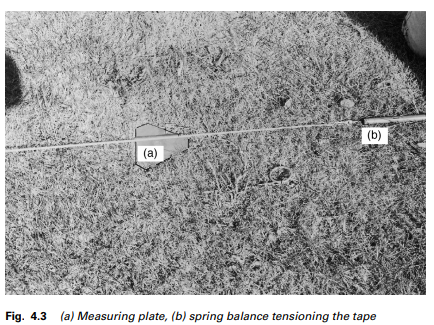

(3) Spring balances are generally used with roller-grips or tapeclamps to grip the tape firmly when the standard tension is applied. As it is quite difficult to maintain the exact tension required with a spring balance, it may be replaced by a tension handle, which ensures the application of correct tension.

(4) Field thermometers are also necessary to record the tape temperature at the time of measurement, thereby permitting the computation of tape corrections when the temperature varies from standard. These thermometers are metal cased and can be clipped onto the tape if necessary, or simply laid on the ground alongside the tape but must be shaded from the direct rays of the sun.

(5) Hand levels may be used to ensure that the tape is horizontal. This is basically a hand-held tube incorporating a spirit bubble to ensure a horizontal line of sight. Alternatively, an Abney level may be used to measure the slope of the ground.

(6) Plumb-bobs may be necessary if stepped taping is used.

(7) Measuring plates are necessary in rough ground, to afford a mark against which the tape may be read. Figure 4.3 shows the tensioned tape being read against the edge of such a plate. The corners of the triangular plate are turned down to form grips, when the plate is pressed into the earth and thereby prevent its movement.

In addition to the above, light oil and cleaning rags should always be available to clean and oil the tape after use.

Comments are closed